|

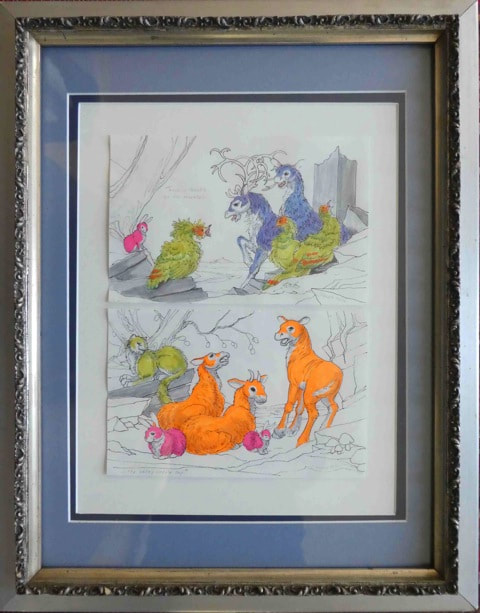

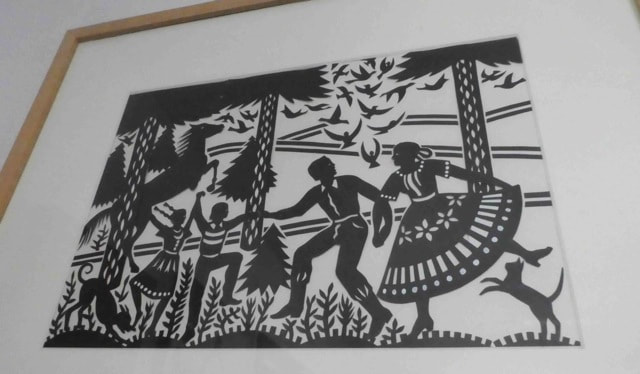

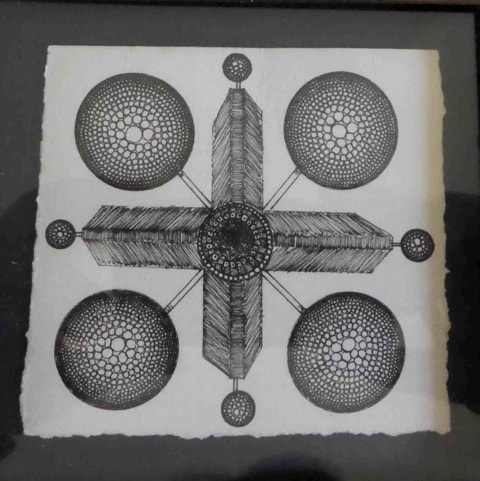

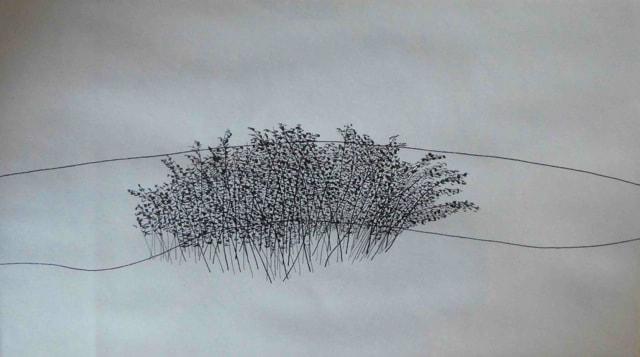

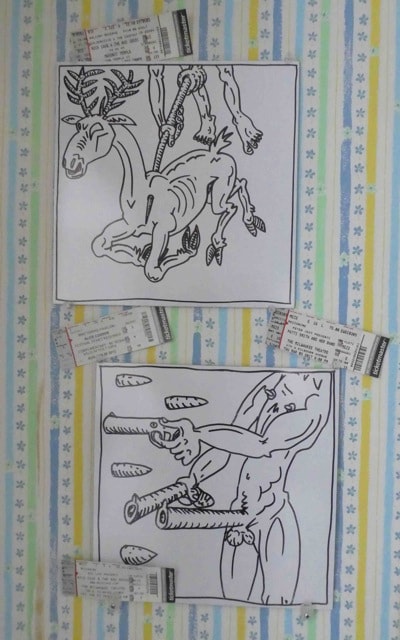

After leaving the Haggerty Museum of Art, Nicole Reid managed Milwaukee’s Tory Folliard Gallery for ten years. She met her husband there and moved to Racine in 2007. Today she enjoys spreading her love of arts and crafts to seniors living in memory care. A passionate supporter of arts and cultural organizations, Reid discusses her art collection and how it came about. The living room corner above the Reid’s TV. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. Having worked in the arts for many years, first at the Haggerty Museum of Art, then at the Tory Folliard Gallery, I’ve been extremely fortunate to have formed friendships with many great artists who have graciously gifted me artworks to help make my collection somewhat significant. However, I won’t discuss these works in favor of focusing on the works that I have purchased throughout the last 20 years. I never set out to own an art collection. I’ve always just bought what I liked. I can categorize my collection in three segments—works on paper, lowbrow, and bunnies. Laurie Hogin studies in pen and ink. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. The majority of my collection consists of works on paper—for the practical reason that they tend to be less costly than a canvas, but also because I have an affinity for prints and drawings. There are many artists whose paintings I cannot afford but whose small sketches and studies I can afford. Such works include fantastic pen and ink studies by Laurie Hogin and a small pencil sketch by Elizabeth Shreve—two fabulous women whose paintings are beyond my means. Says Reid of this favorite, “Imagine this paper cutout by Charles Munch in red and yellow!” Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. Another favorite painter of mine is Charles Munch. While he is known as a colorist, I own one of his early black and white paper-cutouts. It features a family dancing in the woods with the animals. He used the paper cutouts to create smaller, two-color reproductions. The print he made from my cutout was done in red and yellow, a combination that causes me to gag a bit. I much prefer my black and white original. Other notable mentions are a beautiful John Colt watercolor and a Michael Noland gouache of a dilapidated car, poetically titled, The American Dream Re-visited. I am especially drawn to drawings and block prints. I like the simplicity of black and white, ink on paper. For instance, I love the woodcuts of Robert Von Neumann that show burley fishermen hoisting nets and battling the elements. One of my favorite paintings at the MAM is Robert Motherwell’s painting of Two Figures with Stripe. The elegance that can be evoked through a single black brushstroke amazes me. I never succeeded in art because I never knew when to stop. A pastel drawing in my hands quickly becomes an overworked blur. Mark Ottens ink drawing is only 3-inches wide. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. Minimalism was never my style, but I am attracted to it in small doses. For instance, another favorite in my collection is a mezzotint by friend and former coworker, Paula Schulze, called The Orb. It is truly just that—a perfect circle, no more than two inches in diameter, with a thin ring around it. I was completely attracted to its simplicity. I recently purchased a Mark Ottens ink drawing, only three inches square, that exemplifies his manic and measured geometric tendencies. I also have a small pencil drawing by Scott Espeseth featuring a mysteriously smoking bucket. I love his realistic renderings because they come paired with a peculiar perspective. Drawing by an unknown artist of Dogwood at Rabbit Bay. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. My most recent purchase was from an antique shop in Michigan. It is another deceptively simple black and white drawing by an unknown artist. I would have purchased it regardless of its title, but Dogwood at Rabbit Bay helped seal the deal because I have a great affinity for the long-eared creatures. More about that to come. My monochromatic artworks are hung salon style in combination with some very colorful works. Friends often say our house is like a museum because nearly every nook and cranny is filled with art and other collectibles. I think it is less ‘art museum’ and more ‘House on the Rock.’ Panels from a Heimo Wallner mural. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. One of my very favorite works in my collection, which was one my first major purchases, is a watercolor painting by Fred Stonehouse. It is a self-portrait on vintage floral wallpaper with an assortment of human organs floating about and the word ‘fuck’ streaming from his mouth like a red ribbon. In addition to its fine execution, I was drawn to its self-deprecating humor. I guess I have a skewed sense of humor at times. This is how my lowbrow collection formed. Along these lines is a collection of three drawings by Austrian artist, Heimo Wallner, that feature the antics of his signature naked aliens. One of them has a gun-shaped penis, another is slaying a deer and another hunting a man with deer antlers. I bought these many years ago because I thought they were funny. Now I find it funny that I found them to be so funny! Also in my lowbrow collection is a painting on canvas of a disgruntled gutter punk by Chris Miller and two rather unappealing female portraits painted by Judith Ann Moriarty from her Clampett Series, subtitled Real Women Pack Heat. Another work that embodies my off-kilter sense of humor is a gun-shaped pillow. These works are on display in a spare bedroom alongside a gold and black spray painted stencil piece by New York muralist, Logan Hicks. With the exception of the Stonehouse, I purchased these works from Milwaukee’s Lucky Star and Hotcakes Galleries back in the day. The mantel featuring Jeremy Wolf's hare mask. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. Nicole's bunny wall of drawings, etchings and other reproductions. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. As I mentioned before, I have a growing collection of rabbit tchotchkes and rabbit-themed artworks. Our mantel is a rabbit shrine with the centerpiece being a large papier-mâché hare mask by sculptor, Jeremy Wolf. It is mounted on the wall like a trophy head. Below it are various rabbit figurines like an antique stuffed Steiff toy, a beeswax bunny candle, a cookie jar and a piece of driftwood remarkably resembling the animal. Next to the mantel is my wall of 2D bunnies, hung salon style, including a pencil drawing and a few etchings by various local artists, a ceramic tile, an old English tapestry reproduction, and perhaps the most famous hare in art history—a reproduction of the famous Durer print. Nicole's Easter cabinet is filled with bunnies. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. On and endnote, one of the very first encounters I had with my now husband, metal sculptor, Bill Reid, also involved a rabbit. He was delivering new works to Tory’s gallery and brought in a monstrous sculpture featuring a life-sized man, laying on his back, being mauled by a giant, saber-toothed rabbit. My first thought upon seeing this abomination was, “What sick mind would come up with that?” Turns out we share the same sense of humor. The Rabbit Eating Astronaut holds a place of honor in our living room. While my bunnies are at times in friendly competition for display space with Bill’s sculptures, we’ve been able to maintain a happy balance for 13 years now. The kitchen wall features several drawings, including one Nicole's brother did when he was a boy. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved ~Nicole Reid, December 2020

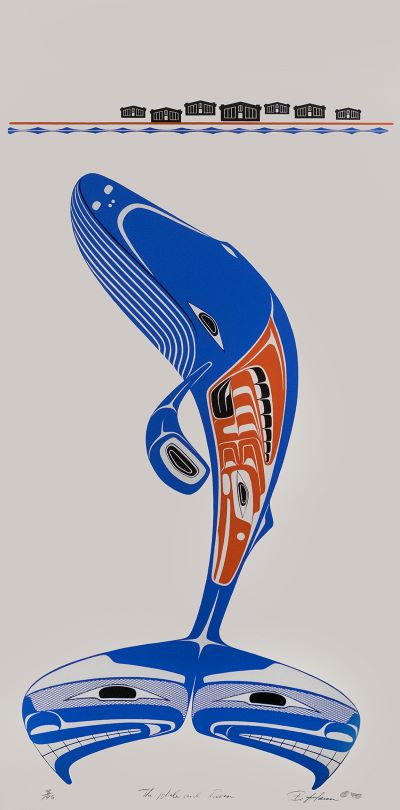

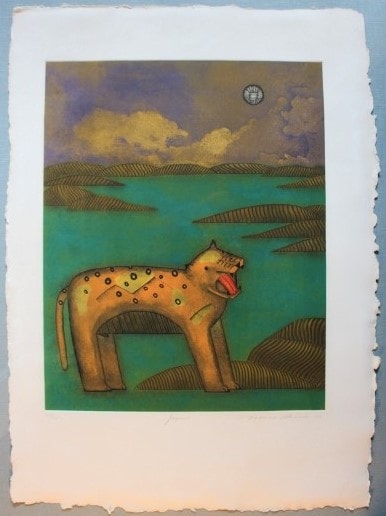

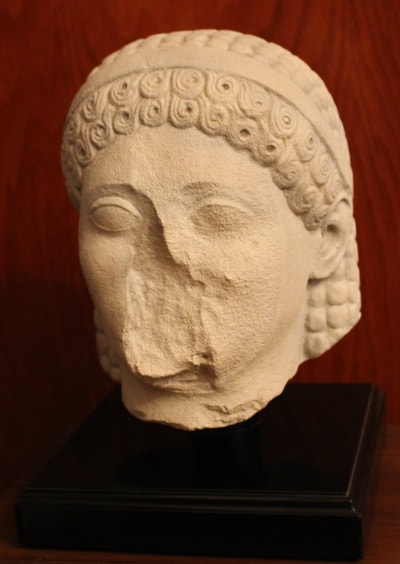

Editor’s Note: Bob Sieger is respected in the artworld. Originally from Kenosha, he worked in the Antiquities Conservation Department at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles for many years. More recently, he brought his expertise back to Milwaukee where he consults with local museums and private collectors on mounting and other specialized needs. Sieger also assisted with facility design during the Guardian building renovation. He recently told me about his personal art collection and provided preservation tips learned from his experience at the Getty. Part I – Personal Collection What do you collect and why? My collection is very small; everything in it was acquired because it appealed to me and, importantly, because I could afford it. It's a mix of things, sculpture; prints; pastels; paintings-oil, acrylic, and gouache; photographs; a few decorative arts furniture pieces; and antiquities, primarily artifacts. Every piece I own evokes memories and emotions: people; places; periods in my life. To me it's similar to walking past a bookcase and having one particular title take me back to the work: the story; the style; the time; the place; everything that made me read and keep that book. That, to me, is one of the best things about owning art; each piece is a part of personal history. The Whale and the Raven by Barry Herem is one of the first pieces Sieger purchased. Photo courtesy of Stonington Gallery and the artist. All rights reserved. I don't know when I actually began what could be termed 'collecting.' Like many people, when I was in school it seemed as though I would move every six months or so. I think maybe when I started being careful to not lose any art during a move could be construed as the starting point. Keeping and caring for the pieces I owned became important. I never consciously attempted to amass a collection; it was always about the individual piece. Sometimes it was the place, like a tiny gallery in Sitka, Alaska where, in 1982, I purchased a serigraph titled, "The Whale and Raven," animals sacred to all Native Alaskan tribes. Or 1993, in a park outside the Bazaar De Sabado in Mexico City where I bought a beautiful print titled "Jaguar" from the artist, Mario Romero, who was showing his work in a small temporary stall. At the time of the purchase in Sitka I had no understanding of the importance of provenance. For this reason, I got no information on the artist or their work from the gallery. The signature on the piece is illegible, and although I've tried to find information online, I hadn't been able to determine the name of the artist. The editor of this piece, Christine Anderson, was able to find the artist. His name is Barry Herem and he works in wood, glass, paper and steel. Jaguar, print by Mario Romero purchased in a market in Mexico City. Photo courtesy of Bob Sieger and the artist. All rights reserved. How do you safely display and/or store your collection? I attempt to follow, as closely as possible, the museum display and storage standards of trying to maintain an ambient temperature of around 70 degrees, and a RH (Relative Humidity) of 50%. I'm also very conscious of keeping any sensitive pieces away from sunlight and limiting their exposure to UV. With a broad mix of objects there isn't any perfect, maintainable climate; some pieces, like metal sculpture do best in a low RH, 30-40%. Other pieces, like works on paper and wooden objects would ideally have a somewhat more humid environment. One of the most important factors in displaying or storing art is that the conditions remain relatively stable, avoiding rapid changes in temperature and RH. What has been most challenging for you in developing your collection? The primary constraint to my collecting, which is a blessing and a curse, is having limited resources to purchase art. This is not all bad because I tend to be a bit of an impulse buyer and have experienced buyer's remorse on a few occasions. Do you have advice for new collectors? I would advise anyone thinking of beginning to collect to buy what you love. Keep records of all the information you can gather about the artist and their career. And keep the receipt. If you have the time and the means learn as much as you can about art in general, and specifically, what you wish to collect. Knowledge of art can only enhance your appreciation. Part II – J Paul Getty Museum What is the focus of the collection you worked with? I worked for many years in the Antiquities Conservation Department at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The Getty's antiquities collection was primarily Greek and Roman, with a few Coptic pieces. The antiquities were almost exclusively 3D objects, art and artifacts, with some 2D material such as frescoes and mosaics. Who was your audience and how did the collection interest them? At the Getty Museum my assumption was always that our audience was generally comprised of that small percentage of the public that had an interest in art and artifacts. The Getty collection was eclectic, originally it was limited to only what interested J. Paul Getty himself. He collected Decorative Arts, Antiquities, Sculpture, Drawings and Paintings. Other than the Antiquities the focus of his collecting was Western European. There was likely a percentage of our audience who were there simply due to a fascination with the Getty name and fortune. It was always gratifying to meet a visitor who was genuinely interested in ancient art and knowledgeable about the pantheon it depicted. An aerocast copy of the original shown to illustrate mount. What was the biggest challenge concerning the collection? How did you safely display and/or store high-risk pieces from the collection?

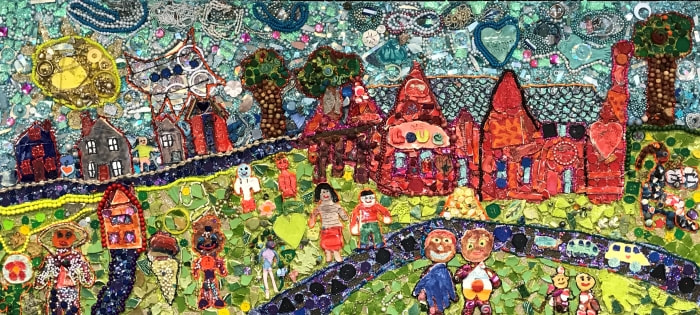

Seismic mitigation. Earthquakes were the single most significant threat to the collection. We were fortunate to be very well-funded. As a result, we had less time constraints than other museums, and we were able to research the best possible ways to protect all types of objects. One result of this research was a base isolation system that was used to decouple large objects from most of the horizontal energy emanating from an earthquake. We designed the isolator and patented it to prevent others from building them for profit. We shared the design and technology, for free, with several other institutions. Later I modified the design and scaled it down in order to use it with much smaller objects as well as small pedestals. All the objects were displayed or stored in a way that safeguarded them as much as possible from earthquake damage. We realized that nothing is truly earthquake-proof, but there are many ways to display or store objects to so as to be very earthquake-resistant. For objects that were robust and could withstand earthquakes as long as they didn't fall, we would attach them to the walls or showcases so they would move with the building during an earthquake. The building had been inspected by seismic engineers and was found to be very strong and unlikely to collapse during an event. More fragile objects needed to supported but decoupled from the seismic input. Our display pedestals were designed to slide rather rock or tip. The only problem with this method was often the curators would move the pedestals closer to the wall and I would have to follow behind them, moving the pedestals away from the walls to allow them to move in all directions. The entire first floor of the Getty Villa Museum was open to the outside air which, due to its proximity to the ocean, was high in salts. To guard against rust which could weaken supports, we generally relied on nonferrous metals, such as aluminum and brass, or stainless steel for our mounts. Like most art museums, the climate was controlled as closely as possible, again trying to maintain an even temperature and relative humidity. ~Robert Sieger Editor’s note: Randy Crosby is the Chief Administrative Officer for Ovation Communities. Ovation provides a full range of services for Milwaukee seniors, including independent living, assisted living, memory care, short-term rehabilitation care, traditional nursing home care, community-based services for early-onset dementia, and adult day care. In collaboration with Ovation’s Art Committee, Crosby founded and oversees the art | ovation program which gives residents, visitors, and staff the opportunity to enjoy curated, rotating art exhibitions in several galleries. Ovation has a large permanent art collection which is thoughtfully placed throughout its campus overlooking Lake Michigan. Recently, Randy took the time to tell us why art is so important to his community. Mosaic by Chai Point seniors in collaboration with children from local schools. Photo courtesy of Ovation Communities. All rights reserved. Randy Crosby: I like to think of art as a bridge. A bridge to richer lives, to community, to opportunity A painting by Miriam Stephen Photo Courtesy of Ovation Communities and the artist. All Rights Reserved. Stained Glass panel by Suzanne Derzon. Photo Courtesy of Ovation Communities and the artist. All Rights Reserved. Photo Credit Hainey Photography. A painting by Clarey Wamhoff. Photo Courtesy of Ovation Communities and the artist. All Rights Reserved. This idea is reflected in Ovation Communities’ art program, art | ovation. This innovative program exhibits art from Ovation’s permanent collection, as well as loaned art from local artists and collectors. The sharing of art resonates with all Ovation stakeholders – residents, guests, employees, volunteers, donors – and inspires them to embrace life and the Ovation experience. A mixed media painting by Calman Shemi. Photo Courtesy of Ovation Communities and the artist. All Rights Reserved. For those who live and work at Ovation, art exhibitions enrich their lives on an ongoing basis. Each new exhibition not only provides an amazing aesthetic experience, but also provides a fresh springboard for discussions and social interactions. All this creates a “buzz” that energizes the whole community. A recent exhibition featured resin sculpture by Tony Spolar of Spolar Studio. Photo Courtesy of Ovation Communities and the artist. All Rights Reserved. Currently, Ovation Chai Point is exhibiting Duets, paintings and prints by Schomer Lichtner and Ruth Grotenrath. Photo courtesy of Ovation and The Warehouse. All rights reserved. Walking Sticks from around the world from the collection of Shirley Langer. Photo Courtesy of Ovation Communities. All Rights Reserved. For members of the broader community, art | ovation provides several ways to get involved in Ovation life. One way is to loan art that one has collected or created, as shown with our current Duet exhibition of Schomer Lichtner and Ruth Grotenrath loaned by Jan Serr and John Shannon of The Warehouse and Guardian Fine Art Services, a recent poured resin sculpture exhibition by Tony Spolar of Spolar Studio, and a walking stick exhibition from the collection of Shirley Langer. Another way to get involved is to attend special events related to related to the exhibitions. We hope to resume our popular opening receptions in the post-COVID19 world. Ovation hopes to resume their festive art opening receptions when conditions are safe post-COVID19. Photo Courtesy of Ovation Communities. All Rights Reserved. At Ovation Communities, art holds a place of honor. It enriches us, inspires us, and invites us to live life to the fullest. At Ovation, art is a bridge to good things. ~Randy Crosby, November 2020 Photo Courtesy of Ovation Communities. All Rights Reserved.

Roxy Paine | Cleft from the series Dendroids | 2018 stainless steel | 444 x 550 x 480 Photograph courtesy the artist, Kasmin Gallery, New York and Sculpture Milwaukee. All rights reserved. Phototography: Kevin J. Miyazaki/Sculpture Milwaukee Sculpture Milwaukee is a non-profit organization transforming downtown Milwaukee’s landscape every year with an annual outdoor exhibition of world-renowned sculpture that serves as a catalyst for community engagement, economic development, and creative placemaking. Privately funded and open at no cost to visitors, Sculpture Milwaukee makes sculpture accessible for everyone to enjoy. Sculpture Milwaukee believes great art has the power to rouse individuals, bring people together and make Milwaukee an even better place. And Guardian agrees! Guardian is a proud sponsor of Sculpture Milwaukee's Sculpture Talks. Curated by Deb Brehmer of the Portrait Society Gallery, the talks offer the public an inside look at how artists, collectors, and the community come together in the spirit of Public Art. So far, two of the 2020 Sculpture Milwaukee Sculpture Talks are online and can be found HERE:

Maggie Sasso | Too Much Sea for Amateurs—Marooned | 2016

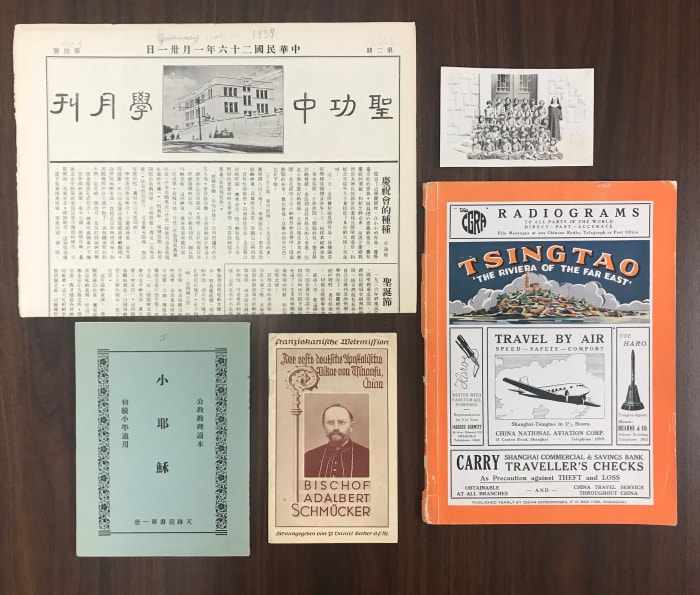

outdoor rated coated polyester fabric, steel, conduit pipe, pipe connectors and feet, Velcro, light fixture | 204 x 144 x 120 inches Photograph courtesy of Sculpture Milwaukee and the artist. All rights reserved. Phototography: Kevin J. Miyazaki/Sculpture Milwaukee The steeples of two landmarks on Milwaukee's south side: St. Joseph Chapel and the former St. Lawrence Church, now home to Notre Dame School of Milwaukee. Over the years, many of the sisters of SSSF taught at St. Lawrence and students crossed the street to minister in Chapel as altar servers at morning Mass. Downtown Milwaukee and Lake Michigan can be seen in the background. Photo courtesy of SSSF. All rights reserved. After a disastrous fire of the original motherhouse in Milwaukee’s Burnham Park neighborhood, the School Sisters of St. Francis rebuilt their motherhouse, St. Joseph Convent in 1891. Over the years, more handsome buildings were added to the campus, including the magnificent Italian Romanesque Revival St. Joseph Chapel completed in 1917 and the Sacred Heart retirement home was renovated more recently. Since its founding, the SSSF have preserved Archives for study by the religious community, relatives of the sisters, and for scholars and members of the public. The rich trove contains works published by members of the SSSF community, reference materials, historical documents, textiles, objects, and more. Eva Stefanski, archivist for SSSF recently discussed the diverse collection and her ongoing work to preserve it. Sister Julie Knotek, unidentified sister, Sister Ann Marie Dressler and Sister Frances Recker (left to right) at St. Lawrence School across Layton Blvd. from St. Joseph Convent, Milwaukee. Photo courtesy of SSSF. All rights reserved. Current display of items in the Archives from the original Motherhouse in Campbellsport. Photo courtesy of SSSF. All rights reserved What is the focus of the collection you oversee? The School Sisters of St. Francis have a long and rich history lasting almost 150 years. The worldwide membership of the community marked its peak of 4,140 members in 1965, and today, with roughly 640 sisters and 170 lay associates worldwide, the congregation continues to serve in North America, Central and South America, Germany, Switzerland, India and Tanzania. The Archives focuses is on preserving materials that chronicle that history along with documents and artifacts that demonstrate the mission, charism, and administration of the community today. We preserve the materials to aid in the congregation’s current planning and decision making as well as to illustrate the history of the community and enable genealogical and historical research. Mother Corona with the faculty of St. Joseph Middle School in Tsingtau, China in 1936. Photo courtesy of SSSF. All rights reserved Who is your audience and how does your collection interest them? Our audience is more varied than one might initially think. While many of our patrons are the Sisters themselves, we get many other types of requests. People often don’t realize that the Sisters lead accomplished professional lives just as lay people do. We are contacted about books they have written, music they have composed and recorded, and art they have created. Additionally, the Motherhouse, the chapel and the surrounding buildings are a historic landmark, so we get many questions about the history of the buildings and grounds as well as the architecture. Also, many requests come for more information about the history of different missions all over the country. The history of the Sisters is deeply embedded in the history of many other parishes, schools, hospitals and communities. Finally, we support frequent genealogy requests. Many lay people with ancestors who belonged to religious congregations want to understand the lives and accomplishments of these women. View of St. Joseph Chapel from the loft. Photo courtesy of SSSF. All rights reserved. What has been the biggest challenge concerning the collection? While working with an international collection is exciting, it’s also challenging. The foreign provinces such as Germany and Honduras have their own archival material in addition to what we have in our collection. Visibility across collections is low, so it can be hard to know where gaps exist and how all of the materials fit together to tell the larger story. Until we are fully able to increase access through digitization, the only way to get the full impact of the scope of our collection is to travel to all of the collecting sites. Alvernia High School Chicago Students lining up for lunch at Alvernia High School in Chicago in 1943. The all-girls school was the first that the School Sisters of St. Francis sponsored and built, opening in September 1924. Photo courtesy of SSSF. All rights reserved. How do you safely display and/or store high-risk pieces from the collection? In Archival work, it is all about what we call “archival housing”. This term refers to the products and materials we use to store and maintain pieces in the collection. Archival housing is not just for rare and fragile items – it ensures the longevity of even simple business documents through the use of things like acid-free folders and boxes. Disaster planning is also critical. Finding the best locations to store collections includes understanding the risks around the potential for things like leaky pipes and mold and having a process that enables you to act quickly if risk becomes reality. Photo and paper ephemera from the Mission in Tsingtao, China in the 1930’s and 1940’s. Photo courtesy of SSSF. All rights reserved. Archival Storage Boxes help preserve fragile documents, photographs, and ephemera. Photo courtsy of SSSF. All rights reserved. What advice do you have for collectors who are just getting started?

My advice for collectors is less about collecting and more about preservation. As an archivist, one of my primary concerns is how to ensure the longevity of the collection under my care. This should be a concern of any collector. Take time to understand the materials that compose what you are collecting and learn about the best conditions for storage and display such as how much light, humidity, and heat are appropriate. Consider not collecting a piece if you are not equipped to care for it or donating a piece to an institution that has the means to ensure its care. Decide early if you want your collection to outlive you and take measures along the way to ensure it will last for many years to come. ~Eva Stefanski, Archivist for School Sisters of St. Francis, October 2020 Editor’s note: Prior to the pandemic, I had the opportunity to tour the campus with archivist Eva Stefanski and Alfons Gallery director Valerie Christell. The historic buildings are filled with beautiful architectural details and fine art made and collected by the sisters. Since all buildings are closed to visitors for safety reasons, explore the SSSF website to learn more about their leadership in the arts and view their video tour of St. Joseph Chapel. MIAD (Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design), located in Milwaukee’s Historic Third Ward, is Wisconsin’s only four-year, private college of visual art and design. Founded in 1974, it is the successor to the venerated Layton School of Art. MIAD is a member of the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design (AICAD), a consortium of 42 leading art schools in the United States and Canada. MIAD currently serves 866 full-time students, 600 pre-college students, and 250 students in outreach and special programs. MIAD has been in the current location at 273 E. Erie Street in Milwaukee since 1992. Photograph courtesy of MIAD. All rights reserved. MIAD has two nationally recognized museum galleries on campus, The Brook Stevens Gallery and the Layton Gallery. We recently had the opportunity to speak with MIAD’s gallery director Mark Lawson and gallery manager Steven Anderson about the unique opportunities and challenges offered by the collections they oversee. These include The Layton Collection, the MIAD Collection, the Guido Brink Collection and three Design Collections. What is the focus of the collection you oversee? Mark Lawson: It is really several collections. The mostly fine art components of the collection can be essentially broken down into three segments. The Layton Collection came from the Layton School of Art which was active until 1974 and eventually evolved into MIAD. The MIAD Collection is everything from 1974 onward and the Guido Brink Collection. Artwork from the MIAD Collection is on view throughout MIAD’s campus, including Martin and Malcolm, 2016 a digital print by George Lum and Carousel Cookies, paint and gold leaf on board by Elyse Fehrenbach. Both artists are MIAD alumni. Photograph courtesy of MIAD. All rights reserved. Paintings from the MIAD Collection are on view throughout MIAD’s campus, including View of the Third Ward from MIAD, an oil on board painting by 2019 graduate Ivan Vasquez. Photograph courtesy of MIAD. All rights reserved. MIAD’s Layton Collection contains paintings, sculptures, works on paper, and historical objects such as these linoleum and woodcut blocks used for printmaking. Photograph courtesy of MIAD. All rights reserved. Part of our holdings include three design collections, the Keyes Camera Collection which has about 300 mostly novelty cameras, all cataloged, the Grassl Collection which contains many 1000’s of vintage ads from magazines and is only 10% catalogued, and the Product Design Collection which has about 500 objects ranging from refrigerators to lawn care tools, to radios and boat motors. The entire Product Design Collection has been catalogued. MIAD’s Product Design Collection contains vintage and contemporary works. Lawson grouped these examples to depict a “sort of youthful exuberance from every decade.” Photograph courtesy of MIAD. All rights reserved. This original Thomas Edison phonograph is an important historical artifact as the first record player for home consumers. It plays wax cylinders and still operates. Photograph courtesy of MIAD. All rights reserved. MIAD’s Product Design Collection contains important design examples such as Evinrude boat motors. Photograph courtesy of MIAD. All rights reserved. Who is your audience and how does your collection interest them? Mark Lawson: Our audience for the different portions of the collection varies somewhat. Our MIAD college community of students, faculty, staff and alumni are our primary audience for much of the collection. One of the primary purposes for the Product Design Collection is to create exhibits about this genre. As such it has been seen by the general public both at MIAD and at other venues to which we’ve loaned various items. A view from the Brooks@20 exhibition in celebration of the 20th anniversary of the Brooks Stevens. Using didactic material shows context of design ideas and promotions. The car was loaned for the special exhibition. Photograph courtesy of MIAD. All rights reserved. Another view from the Brooks@20 exhibition in celebration of the 20th anniversary of the Brooks Stevens Gallery at MIAD. The car was loaned for the special exhibition. Photograph courtesy of MIAD. All rights reserved. Each of MIAD’s collections are used for teaching purposes. This year, the 2020 Senior Exhibit features posters that illustrate graduating students’ projects. Click HERE to view the virtual exhibition. Photograph courtesy of MIAD. All rights reserved. What has been the biggest challenge concerning the collections? Steven Anderson: Keeping the ever-evolving inventory of the art and design collection items up to date, with images, and maintaining proper storage without a registrar. However, a newly renovated collections storage space, the acquisition of collections registration software, and an intern to help re-catalog the collection as it moves to its new home, will all help to solve these challenges. MIAD’s newly built-out Collection Storage has independent climate control and is outfitted with LED fixtures. Photograph courtesy of MIAD. All rights reserved. MIAD’s new Collections Storage area is in the process of being set-up. The blue tape indicates future placement of powder-coated shelving with coroplast liners. Photograph courtesy of MIAD. All rights reserved. Mark Lawson: As college gallery operation, our primary mission is to orchestrate exhibitions for our galleries. As such, we do not have designated staffing, such as a registrar, to deal largely with collection issues. This being the case, all of our work in cataloging and care for the collection has been done when we had the time and budget to address these issues. It has only been recently that this situation has improved and been supported with added budget and attention by the college. How do you safely display and/or store high-risk pieces from the collection? Steven Anderson: In terms of display, we no longer use wire to hang artwork because we have experienced a weakening and even breakage over time. Generally, we use two “D rings” and either two corresponding wall hangers or security mount brackets. If the artwork allows for it, cleats are also a great way to hang heavy objects. Most valuable items are displayed in offices, conference rooms and highly visible public areas. Sculpture and design objects are placed under an acrylic vitrine unless the object is too large, such as a refrigerator, stove or car. Stanchions are then the best option and are often used in our gallery exhibits. Sometimes signage is needed to help inform the viewer of challenging, disturbing or even potential hazards concerning the artwork or objects being displayed. Acrylic vitrines are used to safely display objects throughout MIAD’s campus. Heavier works are hung with d-rings or cleats rather than wire. Photograph courtesy of MIAD. All rights reserved. Our renovated Collections Storage and Presentation Space allows for archival storage and a new exhibit area which will be available and visible to the MIAD community and general public. We will be using powder coated industrial shelving, rolling painting racks, flat files and a variety of archival materials to aid in protecting design objects, sculpture and 2d art. We often use polypropylene coroplast sheets, ethafoam, buffered and un-buffered paper, Tyvek, natural cotton or linen fabric, acid-free mat board and foam core among many other materials depending on the need. The new space is also equipped with its own independent environmental HVAC system to control the temperature and humidity. There are many sources of information online regarding best practices for storage, handling and display. We often refer to PACCIN (Preparation, Art handling, and Collections Care Information Network) if we are unsure of something or we reach out to others in the local museum community. What advice do you have for collectors who are just getting started? Mark Lawson: Stamps are easier. Seriously, collect what you love when it comes to art. This may not be the most profitable way to collect, but it’s the most satisfying. Keep good records of when you buy things and from whom, and as much as you can gather about the artist or designer. It is a given that you’ll forget much of this as the years pass. All collections are more valuable and comprehensive when you have this information along with the artifacts. Installation view of guest curator Danny Volk's antique typewriter collection in the exhibition "Mrs. Lincoln, What Did You Think of the Play" held at MIAD in the spring of 2020. Volk has an extensive antique typewriter collection. Photograph courtesy of MIAD. All rights reserved. ~Mark Lawson, Director of Galleries at MIAD

~Steven Anderson, Gallery Manager at MIAD Lois Bielefeld is a series-based artist working in photography, audio, video, and installation. Her work continually asks the question of what links routine and ritual to the formation of identity and personhood. Editor's note: we originally invited Lois to talk about her collection of local artwork, after getting tantalizing glimpses in the background of her House, Hold series. However, after learning that she "collects" hundreds of portraits to make her series-based work, we wanted to learn more about her process. Self-portrait by Lois Bielefeld. Photograph courtesy of the artist. All rights reserved. Currently splitting her time between Chicago and Los Angeles, Lois was born in Milwaukee, WI and has lived in Rochester, Brooklyn, and Oakland. She is working on her MFA (2021) at California Institute of the Arts. Lois is a recent empty nester as her daughter attends the University of Minnesota. Besides photography, she feels passionate about traveling, hiking, eating, swimming and bicycling adventures with her wife. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art in New York City, the Museum of Wisconsin Art, Saint Kate Arts Hotel, The Warehouse Museum and The Racine Art Museum in Wisconsin. Bielefeld has shown at The International Center of Photography in New York City, The Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, The Charles Allis Art Museum, and Portrait Society Gallery in Milwaukee. What do you collect and why? In 2008 I started my first series-based work, The Bedroom. I was interested in how this intimate space reflected a person and how this manifested in the resulting photograph. This was the beginning of me collecting although I didn’t realize that I was creating these vast collections of photographs around specific themes until recently. The Bedroom evolved into 103 portraits and formulated many of my working practices that I still hold onto today. At the time I saw these portraits as collaborative and a sort of non-scientific ethnographic study. Today I see my work as constructed performances by my participants for the camera. Here is a curious break down of part of my collection by series, time and volume: 2008-2012 The Bedroom (103 photographs) 2012-2013 Conceal Carry (30 photographs) 2012 Lunch Portraits (71 photographs) 2013-2014 Androgyny (58 photographs) 2013-2015, 2017 Weeknight Dinners (86 photographs) 2015-2017 Neighborhood (108 photographs) 2018-current Celebration (11 celebrations) 2018-current New Domesticity (54 photographs) 2019-2020 Broom Studies (120 video studies, 8 hour video piece) 2020 House, Hold (31 photographs) Lois Bielefeld, Steven, Manhattan. 2008 from The Bedroom (the very first photo in the series) Photograph courtesy of the artist and Portrait Society Gallery. All rights reserved. So why? Why am I doing this and why has this act of making within a series in a serial manner so important to me and my practice? I think it is because I’m deeply curious about a specific topic (i.e. gender identity, the evening meal, or domesticity) and I dig into this idea over and over again to become informed by my participants habits, rituals, aesthetic, their thoughts and experiences, and their spaces. Fundamentally, my work continually asks the question of what links routine and ritual to the formation of identity and personhood. I think this is the “why” behind these collections. Lois Bielefeld, Wednesday: Willie Mae. 2013 from Weeknight Dinners Photograph courtesy of the artist and Portrait Society Gallery. All rights reserved. When and how did you get started? I started making photographs when I was a child- initially I had a point and shoot camera that I’d get developed at Walgreens. In high school I was gifted a Pentax K1000 and my folks helped me set up my own black and white darkroom. At this time, I puttered around with the magic of photography-- photographing anything and everything. I studied photography in undergrad at Rochester Institute of Technology graduating in 2002. But it wasn’t until 2008 that I started making series-based works and I think around 2011 that I started to actively pursue my art practice. Lois Bielefeld, Phillip. 2014 from Androgyny Photograph courtesy of the artist and Portrait Society Gallery. All rights reserved. Serra Family Sunday Pasta Lunch. 2018 from Celebration Photograph courtesy of the artist and Portrait Society Gallery. All rights reserved. How do you safely display and/or store your collection? This changes depending on the gallery or institutional space. Each time I show the work it takes on new form based on the context of each space, the current time period shown (what’s happening in the world), and the relationality of other works in the space and the conversation that occurs between them. Sometimes I show the work framed and sometimes I share the work as loose prints hung directly on the wall which gives the prints a much more charged sense of objecthood and vulnerability. Additionally, there is the complex method of archiving digital files. I keep 3 backups of all my files and try to keep one of the three drives offsite. I also do all my own printing (digital) and my framed work currently is overtaking a room at my parent’s home that we’ve recently renamed “The Equipment Room.” Lois Bielefeld, Peter, Eliza, Eula and Abigail. 2018 from New Domesticity Photograph courtesy of the artist and Portrait Society Gallery. All rights reserved. What has been most challenging for you in developing your collection? I think every individual series has its own challenges- sometimes it can be very difficult to find participants, other times I tire of schlepping equipment around, but most often I would say the consistent difficulty is getting the work out there. I love making the work- it gives me a sense of purpose and vivaciousness! But I really don’t care to promote myself, apply to calls, and networking. This labor is the most challenging to me. Lois Bielefeld, Broom Study #11 Still. 2019 Photograph courtesy of the artist and Portrait Society Gallery. All rights reserved. Lois Bielefeld, Broom Study #69 Still. 2019 Photograph courtesy of the artist and Portrait Society Gallery. All rights reserved. Do you have advice for new collectors? For art collection, collect work that moves you- that you keep thinking about and has a staying power. Start by getting familiar with your local art scene by going to the local galleries, different institutions- museums and universities. Ask an artist for a studio visit to get a behind the scenes look at their process and to see the work in person. Supporting the local art scene is so crucial and commendable. And definitely consider the work of students and emerging artists. Lois Bielefeld, May 29: When Lois doesn't have a pocket, she uses her waistband to hold tissues. When Jackie doesn't have a napkin, she wipes her fingers on her sock. 2020 from House, Hold. Photograph courtesy of the artist and Portrait Society Gallery. All rights reserved. ~Lois Bielefeld, September 2020

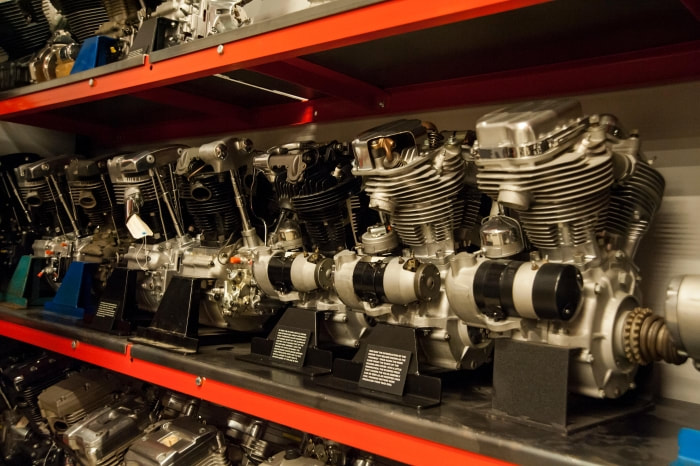

This week’s blog post features an interview with Harley-Davidson Museum motorcycle restorer/conservator Bill Rodencal. Special thanks to HDM’s Tim McCormick for coordinating this interview. On the third floor of the Annex building at the Harley-Davidson Museum in Milwaukee’s Menomonee Valley, the balance of the company’s historic vehicle collection resides. This collection was begun during the earliest days of the Motor Company’s humble beginnings, and at least one bike from each model year of production has been saved. Visitors are allowed to take the elevator from the second floor of the Annex building to the third-floor viewing area and see where the collection is housed. The Archives three-tiered motorized racking system houses over 300 motorcycles on their own individual pallets. Photograph courtesy of Harley-Davidson Museum. All rights reserved. What is this? Welcome to the Motorcycle Storage and Conservation area. This area houses the balance of the company’s historic motorcycle collection. Over 300 motorcycles are stored on individual pallets with open spaces for future growth. These bikes are equally important as the bikes in the museum, we just don’t have room to display them all. The palleted bikes are stored on a moveable racking system developed by a local Wisconsin company. The lower spaces contain machines that are the tallest in height many with windshields, and the upper racks are for shorter bikes due to interference with lighting and sprinkler pipes. The reason for this is to maximize the entire space to store the most possible bikes within the space. The motorcycles can be retrieved by a small forklift that resides in the storage area. A selection of vintage engines stored in the powertrain storage racking. Photograph courtesy of Harley-Davidson Museum. All rights reserved. What is it composed of? The bulk of the machines in this room consist of examples the company has and continues to save from the assembly line since having never been started or run on the road. Others may include styling mockups and prototype vehicles or those added from outside sources including historic race machines, celebrity bikes, bikes used in Hollywood movies, or just motorcycles with important stories or historic motorcycle prowess. How is the area used? In the early days of the Motor Company, the founders believed it important to retain motorcycles to document company history. This is a process that continues to this day. This is a working collection and we frequently collaborate with other internal Harley-Davidson departments and use these bikes for such things as part fitments of service parts on older models, members of the Styling Department use them for ques on future products, or as examples to be copied for licensed product such as die-cast models. The workspace also doubles as an area to prep for upcoming exhibits and outgoing loans. In this area we also prepare, photograph and conserve new vehicles that are added to the collection and well as our powertrain collection of over 160 historic engines and transmission examples. A large motorized turntable with a neutral backdrop serves as a photo studio for creating vehicle photography used in label copy as well as for insurance purposes. A large motorized turntable is used to photograph motorcycles from 10 angles for both insurance purposes and to be used for various company initiatives. Two prototype three-wheeled vehicle serve as the “model” in this photo. Photograph courtesy of Harley-Davidson Museum. All rights reserved. Philosophy of Conservation? As a rule, we practice conservation/preservation. Our goal is to keep the artifacts in a stable condition as close the state we received it in (original or as used by someone) for as long as possible. Artifacts and their condition tell us stories. If you alter an artifact, you’re changing its story. As historians and caretakers, we don’t want to do that. Motorcycles are disassembled and painstakingly cleaned and reassembled without repainting or replating. Occasionally, the Archives Dept. consults with outside conservation experts regarding artifacts that need preservation treatment. The only time the Archives would consider restoring a motorcycle is if that bike were to come into the collection from the outside and had been improperly restored by a previous owner. A 1924 model JD undergoing cleaning and stabilization in the Archives Motorcycle Conservation area. Photograph courtesy of Harley-Davidson Museum. All rights reserved. A 1924 model JD undergoing cleaning and stabilization in the Archives Motorcycle Conservation area. Photograph courtesy of Harley-Davidson Museum. All rights reserved. Motorcycle Conservation. Unlike artifacts made of a single composition, motorcycles are unique that they may contain many different types of materials such as aluminum, steel, leather, cloth or plastic covered wiring or paper gaskets. Many of these require specific conservation techniques and thrive better in different environments. Iron is more stable in very dry air while leather prefers a slightly more humid space. Therefore, a happy medium must be achieved to provide the most optimum long-term storage situation. Tires are filled with compressed nitrogen to reduce the moisture content inside the tire or tube and being eight times denser than compressed air it will stay inflated for longer periods of time. Materials used have also changed over time. Early vehicles were finished with clear or yellow copal varnish like that used by violin makers over the top of the enamel base color. Today modern clear coat paints are used to protect the base finish. All of this must be taken into careful consideration prior to undergoing a successful conservation.

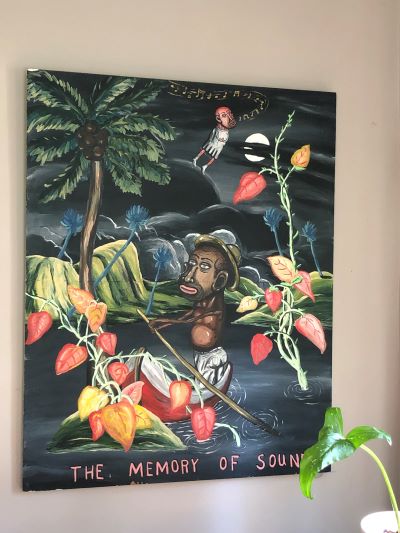

~Bill Rodencal, motorcycle restorer/conservator at Harley Davidson Museum Visit the Harley-Davidson Museum website to read stories from the archives, to learn more about the permanent and special exhibitions, and to see a listing of upcoming events. #HarleyDavidsonMuseum #VisitMKE #VintageMotorcycles #HarleyDavidson #SafeStorage #PreserveYourCollection This week’s blog post features Debra Brehmer, founder and Gallery Director of Milwaukee’s Portrait Society Gallery. Debra Brehmer is an art historian who has taught part time at the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design. She has curated numerous exhibitions and written extensively about art for various publications for more than 20 years. She is a regular contributor to the national art publication, Hyperallergic. She was also a founder and the publisher and editor of Art Muscle Magazine. Debra Brehmer in her kitchen with a painting by Tracy Cirves, Red Crimped Hair, 2019, oil on canvas, 48x36 inches Photo courtesy of Debra Brehmer. All rights reserved. What do you collect and why? I suppose that more than “collect,” I acquire or gather. Collecting sounds too intentional for the work I have amassed. As an art dealer, I’m always looking at art. Every day, whether it is on Instagram or, prior to Covid, making trips to museums, galleries and artists’ studios. My happiest times are when I can linger for full days in museums. I have a lot of artwork from the artists we represent at Portrait Society Gallery. Maybe some of the more telling works are things I acquired prior to owning an art gallery. Let’s start with Fred Stonehouse. It was the 1990s. Many of us lived in Walker’s Point. I was publishing Art Muscle Magazine and going to graduate school and working at the Milwaukee Art Museum. Fred had just graduated from UWM and his studio was on 5th Street. My then partner and I purchased our first art work from Fred. His style was already fully formed. Our painting is called “The Memory of Sound.” I am still able to lose myself within this dreamy tropical river scene. The painting is on a solid wood panel. I always worried that it would fall on one of my toddlers. Fred Stonehouse, The Memory of Sound, 1986, acrylic on board, 60x48 inches. Photo courtesy of Debra Brehmer. All rights reserved. My most cherished objects are from Mary Nohl. I did my master’s thesis on Mary when she was alive and got to know her. When I finished my thesis, she let me pick a painting. When I gave birth to my second child, she also let me pick a painting. Mary Nohl was one of the most exceptional people I have had in my life. Living with her paintings and ceramics reminds me on a daily basis to not care what other people think, to remember that making art is one of the most worthwhile and rewarding endeavors we can engage in, and that being a woman means you will have to bear the weight of discrimination. Mary Nohl, Untitled, 1960’s and revised in the 1990’s, oil on panel, 23x35 inches. Photo courtesy of Debra Brehmer. All rights reserved. I live with art because it is like insulating your home and walls, with reminders of human potentiality. Art making is a distillation of focus and observation. It requires a sensitivity to life. It is also a celebration of beauty and invention. What could be better? Since COVID, I’ve been home so much that I’ve rearranged the art. It is a pleasure to move things and see them anew. I now have this incredible Tracy Cirves painting in my kitchen that literally brings me daily joy. I swear it sheds beams of psychic light. I also have wonderfully oddball objects such as a sculpture made from beaver-chewed wood by David Niec (next to one of his moon paintings), paintings by my friends Kay Knight and Pat Hidson, several Mark Mulhern monotypes, a 1940s Schomer Lichtner that I adore, and a recently acquired repurposed leather textile by Rosemary Ollison, a 2019 City of Milwaukee Artist of the Year. A bureau in Brehmer’s home serves as the base for a vignette of art and objects. David Niec’s "Moonrise at 29 percent, Lake Michigan," 2015, Oil on panel, 14 1/4 x 11 1/4 inches is shown behind a found beaver-chewed log he made into a sculpture. Also shown are Richard Knight’s Building a Box," Mixed media on paper, 20 x 23 inches, and ceramic heads by Claire Loder and Deb Brehmer. Photo courtesy of Debra Brehmer. All rights reserved. When and how did you get started I started collecting in grade school. I was in love with a boy in the 5th grade because he could draw. I would steal small things from his desk: an eraser, a pencil, etc. I created a secret museum under my dresser where I presented the objects with labels and acquisition dates. One time, he actually gave me a pencil drawing. Another formative experience was when I was in middle school. My parents had friends whose son was in art school at UW-Madison. He had brought home his large abstract paintings from his thesis show. When I admired them, he said I could pick one. I still have it. When I was a kid, I had many collections: match books, tiny bars of soap, sugar packages, plastic horses, erasers in the shapes of animals, ceramic animals, troll dolls. How do you safely store your collection and care for it? I am fortunate to have a storeroom in the Marshall Building near my gallery where I can keep things. But storage is always a bit of a problem. Often, people will tell me that they can’t buy something they love because they don’t have room on their walls. I believe it is essential to rotate works. Don’t leave the same things in the same place forever. I would recommend that people find a secure place to store work and then at least once year, shake things up. Move things around. I also collect handmade, crocheted hot pads and mosaic vintage ashtrays. I have not found a good way to store these objects. I wish I could frame every hot pad and do a large wall of them. They were shown in a gorgeous installation at UWM at the Union Art Gallery in a show about artists and dealers’ collections. What has been the most challenging for you in developing a collection? I am drawn to certain types of objects and the biggest challenge is to keep expanding my interests and tastes, to go beyond what I ‘think’ I like. Most of the work I own is figurative. In the past four months, I’ve been drawn to non-objective work with quiet open spaces. I’ve been on an Agnes Martin influenced binge, seeking out work by women artists with that light, precise, meditative touch. (One local example is the textile artist Heidi Parkes). Surely this is symptomatic of our anxious time. I was wowed by the Lenore Tawney show at the Kohler. I’m a relatively new convert to textiles and fiber arts. It is important to challenge your own interests. I am not in the economic bracket to purchase expensive things, but I don’t find that limiting. Regional art and humble objects can be affordable. Do you have any advice for new collectors? If you want something, take the leap. Find a way. Artists often have great collections because they trade with each other. Collecting art is not simply a pursuit of the wealthy. I have a friend who has amassed an incredible collection of smooth round stones. The act of collecting is creative by nature, and thus rewarding. You are committing to beauty and ideas, to expansive languages that are not readily translatable. The best collections are those that leap from high to low: paintings, photographs or sculptures along with unexpected objects and low-priced resale store finds or work by emerging artists. I will do a shout-out to Tim and Sue Frautschi on this and Joseph Pabst. Do not worry about whether something is “good” by anyone else’s standards. Collecting art is personal. It is about your interests, values, memories, ideals, it is about what happened to you last year and how you want to embed those feelings in an object. A painting by Bernard Gilardi interacts with a leather textile by Rosemary Ollison. Photo courtesy of Debra Brehmer. All rights reserved. It is about where you want to travel in your mind. Most importantly, support your local art community. This is satisfying because you are participating in the infrastructure of your own creative sector. You can get to know the artists, visit their studios. It is gratifyingly hands on. ~Debra Brehmer, Portrait Society Gallery, August 2020 #ArtCollector #GuardYourCollection #PortraitSocietyGallery #DebBrehmer #MilwaukeeArtScene #MaryNohl #FredStonehouse #DavidNiec #RosemaryOllison #TracyCirves #BernardGilardi #SecureArtStorage

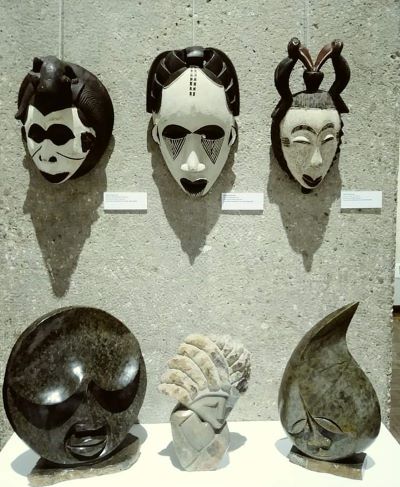

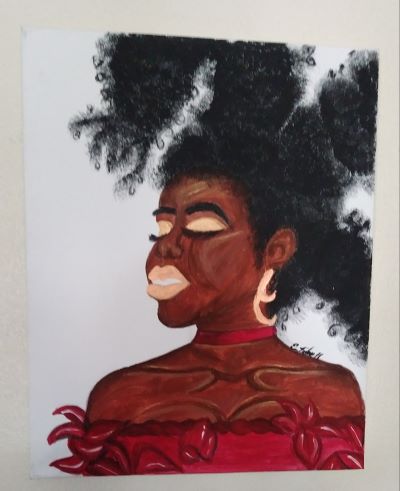

This week’s blog post features art advocate, educator, and, when time allows, artist Jody Alexander. Jody moved back to Milwaukee after living in San Francisco where she studied art history. She worked at the Milwaukee Art Museum and continues to serve on the board of the African American Art Alliance for nearly 20 years. The African American Art Alliance is one of nine support groups at the Milwaukee Art Museum that focus on specific areas of interest within the collection. The AAAA helped secure Kehinde Wiley’s St. Dionysus for the permanent collection. Jody Alexander also taught life skills to students in the Pathways to College program. Jody Alexander at a Gallery NO:105 artists reception. Photo courtesy of Jody Alexander. All rights reserved. In 2010, Jody Alexander founded the organization Blk-Art*History&Culture which teaches children black history by using the art of iconic African American artists. She creates Information Stations at churches, schools, libraries, and community centers with works from her extensive collection of art, books, black memorabilia, and music. Alexander started the pop-up Gallery NO:105 in 2015 and since 2016, she has headed the MARN Mentor program for the Milwaukee Artist Resource Network (MARN). This year’s exhibition will be up through August 28th. She also founded the Sisters of Creativity, a group which “seeks to recognize African-American women who have long been marginalized from the mainstream art world.” Their exhibition A Community of Voices will be on view at the Museum of Wisconsin Art through September 6th, 2020. As Jody said during our interview, “Everything I do is around art.” What do you collect and why? Much of the work I collect is by Wisconsin and regional artists. If it speaks to me, I add it to the collection. I trust my instinct. Margaret Burroughs, Faces A’ La Picasso, a preliminary drawing for the print series. Photo courtesy of Jody Alexander. All rights reserved. Rosemary Ollison, Untitled, ink drawing Photo courtesy of the artist, Portrait Society Gallery, and Jody Alexander. All rights reserved. One special piece is a carved Shona sculpture from Zimbabwe. At the time I couldn’t afford it. I spoke with the owner of the Mhiripiri Gallery in Minnesota who let me take it home after making a deposit. He could see how much I loved it and trusted me to pay for it. It took me a year to pay it off. It became the logo for my organization Blk-Art*History&Culture. Shona sculpture in the collection of Jody Alexander. Photo courtesy of Jody Alexander. I have since purchased more work from him. Some of the work was in the 2019 Sneak Peek Part II: A Look at Private Collections exhibition at the UWM Union Art Gallery. Installation view of Sneak Peek Part II: A Look at Private Collections exhibition at the UWM Union Art Gallery. I also collect Wisconsin artists that I work with. My gallery, Gallery NO:105, organizes pop-up exhibitions, artist markets, and other events featuring artwork by local artists available for purchase. I met Ebony Tidwell at the Black Arts Festival and purchased a painting. I invited her to be in the MARN Mentors program because I could see her potential and loved her work. Ebony enjoys developing her skills with her mentor Della Wells. Rosie Petry is another artist from the program whose potential I saw early on. I am proud of her achieving the Artist in Residence at the Pfister Hotel. Ebony Tidwell, Untitled, acrylic on canvas. Image courtesy of the artist and Jody Alexander. All rights reserved. When and how did you get started? I bought my first piece of African art, a wood sculpture of a fertility doll at a festival when I was 19. I didn’t know what I was buying, but it spoke to me. I later learned I had fertility issues. This wood sculpture of an African fertility doll is the first piece Alexander purchased. Image courtesy of Jody Alexander. All rights reserved. Art always finds me and my collection is always evolving. I just bought a piece by Chrystal Gillon. I scooched another piece over to make room for it. Somehow it all falls into place Miss America Lula Mae Toussant, mixed media assemblage’ by Chrystal Gillon. Image courtesy of the artist and Jody Alexander. All rights reserved. How do you safely display and/or store your collection? I am reluctant to loan things out because there is always a chance for damage. There are some works that I won’t loan because I love them too much. Over the years, some pieces have been featured in a magazine article in Black Women 50+ and on Milwaukee PBS’s program Black Nouveau. I keep wood sculpture out of the light. No direct sunlight on any piece. When I select pieces for my public Information Stations, I wrap everything carefully to keep it safe during transport. I have a guest room where items can be stored safely. I practice safety due to the investment and the fact that it is a blessing to be able to collect. I never, ever buy a piece of art thinking about the resale value. I collect for my own pleasure. I have certain pieces that I never move – they stay in a permanent location in my home and I work in new acquisitions around them. What has been most challenging for you in developing your collection? I don’t have a strategy – each item is a piece of a puzzle that becomes more complete with time. I live in a space that is about 750 square feet and don’t want it to look cluttered. Visitors have told me my apartment looks “curated”. Once a year I have an open house for my Blk-Art*History&Culture collection. When I have these events, I stagger the number of visitors to avoid overcrowding. Do you have advice for new collectors? Stop worrying that collecting art is only for the rich. I am not rich, but I have rich relationships and get great satisfaction going to lectures and exhibitions. A good way to start is by going to the student shows at the Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design or Mount Mary or festivals such as Art Fair on the Square or the Black Arts Fest MKE or local galleries where art is affordable. Go to artist studios. I got this piece from Corey McVey of Milwaukee Potters Guild located in the Marshall Building. Ceramic Platter by Corey McVey. Image courtesy of the artist and Jody Alexander. All rights reserved. The last 20 years have been a wonderful journey. Milwaukee has become a fabulous art hub. I am thrilled to be a part of the Milwaukee art scene. And I love maintaining friendships with the artists I meet. ~Jody Alexander, July 2020 #ArtCollectorInterview #JodyAlexander #AfricanAmericanArt #AfricanArt #ArtandEducation

#PreserveYourCollection #SecureArtStorage |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed