|

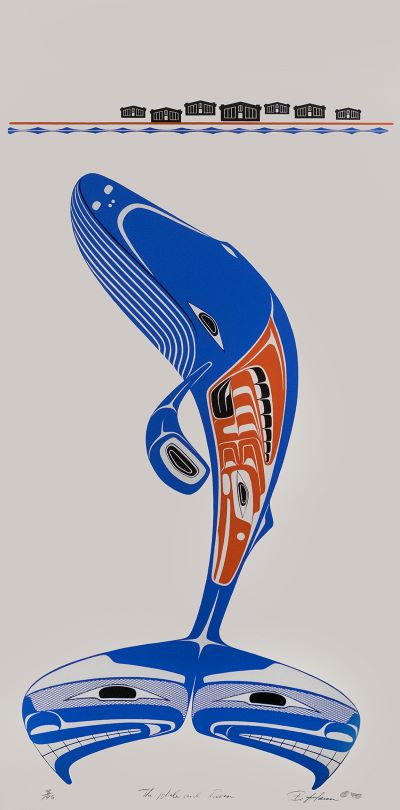

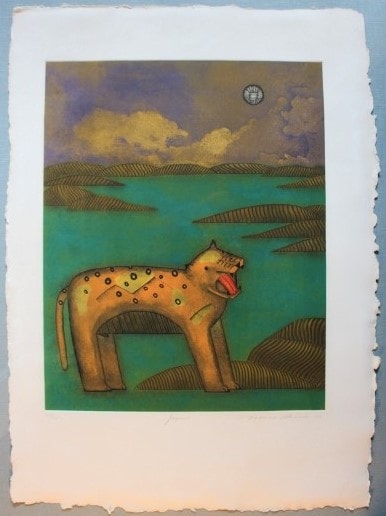

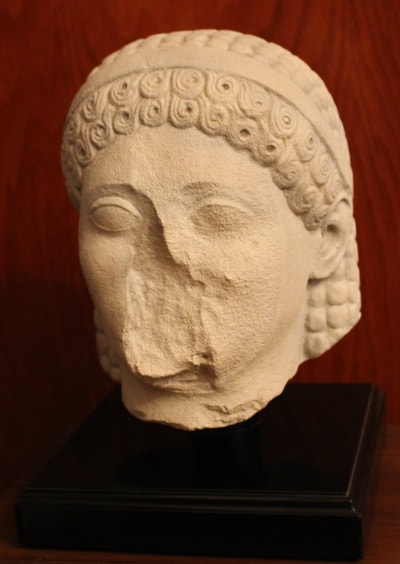

Editor’s Note: Bob Sieger is respected in the artworld. Originally from Kenosha, he worked in the Antiquities Conservation Department at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles for many years. More recently, he brought his expertise back to Milwaukee where he consults with local museums and private collectors on mounting and other specialized needs. Sieger also assisted with facility design during the Guardian building renovation. He recently told me about his personal art collection and provided preservation tips learned from his experience at the Getty. Part I – Personal Collection What do you collect and why? My collection is very small; everything in it was acquired because it appealed to me and, importantly, because I could afford it. It's a mix of things, sculpture; prints; pastels; paintings-oil, acrylic, and gouache; photographs; a few decorative arts furniture pieces; and antiquities, primarily artifacts. Every piece I own evokes memories and emotions: people; places; periods in my life. To me it's similar to walking past a bookcase and having one particular title take me back to the work: the story; the style; the time; the place; everything that made me read and keep that book. That, to me, is one of the best things about owning art; each piece is a part of personal history. The Whale and the Raven by Barry Herem is one of the first pieces Sieger purchased. Photo courtesy of Stonington Gallery and the artist. All rights reserved. I don't know when I actually began what could be termed 'collecting.' Like many people, when I was in school it seemed as though I would move every six months or so. I think maybe when I started being careful to not lose any art during a move could be construed as the starting point. Keeping and caring for the pieces I owned became important. I never consciously attempted to amass a collection; it was always about the individual piece. Sometimes it was the place, like a tiny gallery in Sitka, Alaska where, in 1982, I purchased a serigraph titled, "The Whale and Raven," animals sacred to all Native Alaskan tribes. Or 1993, in a park outside the Bazaar De Sabado in Mexico City where I bought a beautiful print titled "Jaguar" from the artist, Mario Romero, who was showing his work in a small temporary stall. At the time of the purchase in Sitka I had no understanding of the importance of provenance. For this reason, I got no information on the artist or their work from the gallery. The signature on the piece is illegible, and although I've tried to find information online, I hadn't been able to determine the name of the artist. The editor of this piece, Christine Anderson, was able to find the artist. His name is Barry Herem and he works in wood, glass, paper and steel. Jaguar, print by Mario Romero purchased in a market in Mexico City. Photo courtesy of Bob Sieger and the artist. All rights reserved. How do you safely display and/or store your collection? I attempt to follow, as closely as possible, the museum display and storage standards of trying to maintain an ambient temperature of around 70 degrees, and a RH (Relative Humidity) of 50%. I'm also very conscious of keeping any sensitive pieces away from sunlight and limiting their exposure to UV. With a broad mix of objects there isn't any perfect, maintainable climate; some pieces, like metal sculpture do best in a low RH, 30-40%. Other pieces, like works on paper and wooden objects would ideally have a somewhat more humid environment. One of the most important factors in displaying or storing art is that the conditions remain relatively stable, avoiding rapid changes in temperature and RH. What has been most challenging for you in developing your collection? The primary constraint to my collecting, which is a blessing and a curse, is having limited resources to purchase art. This is not all bad because I tend to be a bit of an impulse buyer and have experienced buyer's remorse on a few occasions. Do you have advice for new collectors? I would advise anyone thinking of beginning to collect to buy what you love. Keep records of all the information you can gather about the artist and their career. And keep the receipt. If you have the time and the means learn as much as you can about art in general, and specifically, what you wish to collect. Knowledge of art can only enhance your appreciation. Part II – J Paul Getty Museum What is the focus of the collection you worked with? I worked for many years in the Antiquities Conservation Department at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The Getty's antiquities collection was primarily Greek and Roman, with a few Coptic pieces. The antiquities were almost exclusively 3D objects, art and artifacts, with some 2D material such as frescoes and mosaics. Who was your audience and how did the collection interest them? At the Getty Museum my assumption was always that our audience was generally comprised of that small percentage of the public that had an interest in art and artifacts. The Getty collection was eclectic, originally it was limited to only what interested J. Paul Getty himself. He collected Decorative Arts, Antiquities, Sculpture, Drawings and Paintings. Other than the Antiquities the focus of his collecting was Western European. There was likely a percentage of our audience who were there simply due to a fascination with the Getty name and fortune. It was always gratifying to meet a visitor who was genuinely interested in ancient art and knowledgeable about the pantheon it depicted. An aerocast copy of the original shown to illustrate mount. What was the biggest challenge concerning the collection? How did you safely display and/or store high-risk pieces from the collection?

Seismic mitigation. Earthquakes were the single most significant threat to the collection. We were fortunate to be very well-funded. As a result, we had less time constraints than other museums, and we were able to research the best possible ways to protect all types of objects. One result of this research was a base isolation system that was used to decouple large objects from most of the horizontal energy emanating from an earthquake. We designed the isolator and patented it to prevent others from building them for profit. We shared the design and technology, for free, with several other institutions. Later I modified the design and scaled it down in order to use it with much smaller objects as well as small pedestals. All the objects were displayed or stored in a way that safeguarded them as much as possible from earthquake damage. We realized that nothing is truly earthquake-proof, but there are many ways to display or store objects to so as to be very earthquake-resistant. For objects that were robust and could withstand earthquakes as long as they didn't fall, we would attach them to the walls or showcases so they would move with the building during an earthquake. The building had been inspected by seismic engineers and was found to be very strong and unlikely to collapse during an event. More fragile objects needed to supported but decoupled from the seismic input. Our display pedestals were designed to slide rather rock or tip. The only problem with this method was often the curators would move the pedestals closer to the wall and I would have to follow behind them, moving the pedestals away from the walls to allow them to move in all directions. The entire first floor of the Getty Villa Museum was open to the outside air which, due to its proximity to the ocean, was high in salts. To guard against rust which could weaken supports, we generally relied on nonferrous metals, such as aluminum and brass, or stainless steel for our mounts. Like most art museums, the climate was controlled as closely as possible, again trying to maintain an even temperature and relative humidity. ~Robert Sieger |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed