|

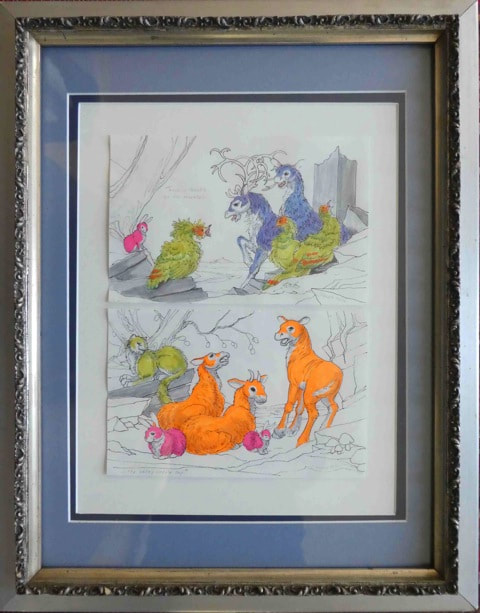

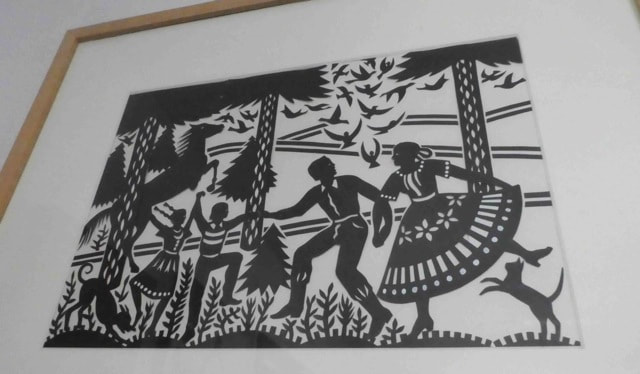

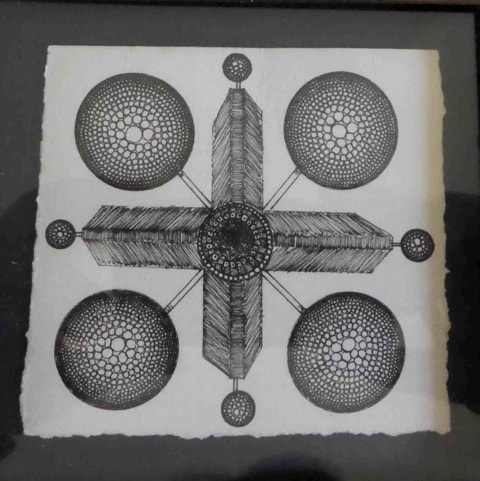

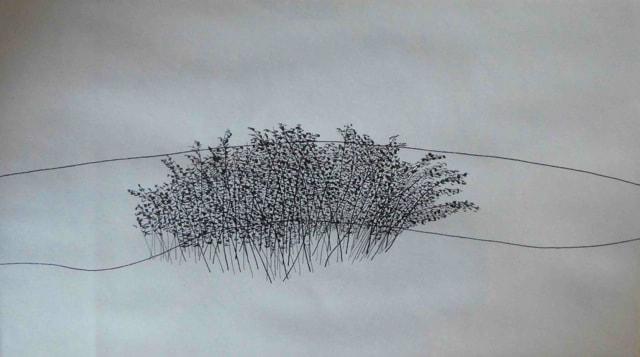

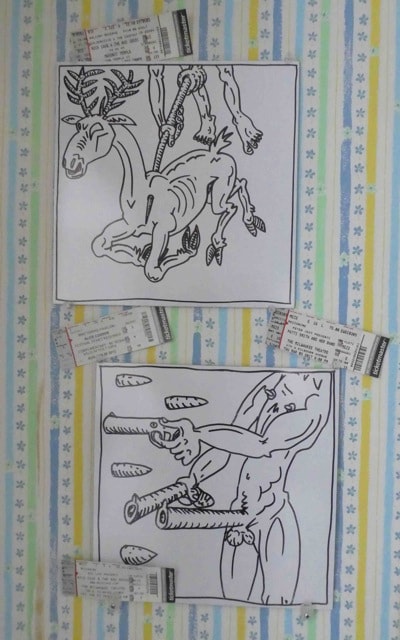

After leaving the Haggerty Museum of Art, Nicole Reid managed Milwaukee’s Tory Folliard Gallery for ten years. She met her husband there and moved to Racine in 2007. Today she enjoys spreading her love of arts and crafts to seniors living in memory care. A passionate supporter of arts and cultural organizations, Reid discusses her art collection and how it came about. The living room corner above the Reid’s TV. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. Having worked in the arts for many years, first at the Haggerty Museum of Art, then at the Tory Folliard Gallery, I’ve been extremely fortunate to have formed friendships with many great artists who have graciously gifted me artworks to help make my collection somewhat significant. However, I won’t discuss these works in favor of focusing on the works that I have purchased throughout the last 20 years. I never set out to own an art collection. I’ve always just bought what I liked. I can categorize my collection in three segments—works on paper, lowbrow, and bunnies. Laurie Hogin studies in pen and ink. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. The majority of my collection consists of works on paper—for the practical reason that they tend to be less costly than a canvas, but also because I have an affinity for prints and drawings. There are many artists whose paintings I cannot afford but whose small sketches and studies I can afford. Such works include fantastic pen and ink studies by Laurie Hogin and a small pencil sketch by Elizabeth Shreve—two fabulous women whose paintings are beyond my means. Says Reid of this favorite, “Imagine this paper cutout by Charles Munch in red and yellow!” Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. Another favorite painter of mine is Charles Munch. While he is known as a colorist, I own one of his early black and white paper-cutouts. It features a family dancing in the woods with the animals. He used the paper cutouts to create smaller, two-color reproductions. The print he made from my cutout was done in red and yellow, a combination that causes me to gag a bit. I much prefer my black and white original. Other notable mentions are a beautiful John Colt watercolor and a Michael Noland gouache of a dilapidated car, poetically titled, The American Dream Re-visited. I am especially drawn to drawings and block prints. I like the simplicity of black and white, ink on paper. For instance, I love the woodcuts of Robert Von Neumann that show burley fishermen hoisting nets and battling the elements. One of my favorite paintings at the MAM is Robert Motherwell’s painting of Two Figures with Stripe. The elegance that can be evoked through a single black brushstroke amazes me. I never succeeded in art because I never knew when to stop. A pastel drawing in my hands quickly becomes an overworked blur. Mark Ottens ink drawing is only 3-inches wide. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. Minimalism was never my style, but I am attracted to it in small doses. For instance, another favorite in my collection is a mezzotint by friend and former coworker, Paula Schulze, called The Orb. It is truly just that—a perfect circle, no more than two inches in diameter, with a thin ring around it. I was completely attracted to its simplicity. I recently purchased a Mark Ottens ink drawing, only three inches square, that exemplifies his manic and measured geometric tendencies. I also have a small pencil drawing by Scott Espeseth featuring a mysteriously smoking bucket. I love his realistic renderings because they come paired with a peculiar perspective. Drawing by an unknown artist of Dogwood at Rabbit Bay. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. My most recent purchase was from an antique shop in Michigan. It is another deceptively simple black and white drawing by an unknown artist. I would have purchased it regardless of its title, but Dogwood at Rabbit Bay helped seal the deal because I have a great affinity for the long-eared creatures. More about that to come. My monochromatic artworks are hung salon style in combination with some very colorful works. Friends often say our house is like a museum because nearly every nook and cranny is filled with art and other collectibles. I think it is less ‘art museum’ and more ‘House on the Rock.’ Panels from a Heimo Wallner mural. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. One of my very favorite works in my collection, which was one my first major purchases, is a watercolor painting by Fred Stonehouse. It is a self-portrait on vintage floral wallpaper with an assortment of human organs floating about and the word ‘fuck’ streaming from his mouth like a red ribbon. In addition to its fine execution, I was drawn to its self-deprecating humor. I guess I have a skewed sense of humor at times. This is how my lowbrow collection formed. Along these lines is a collection of three drawings by Austrian artist, Heimo Wallner, that feature the antics of his signature naked aliens. One of them has a gun-shaped penis, another is slaying a deer and another hunting a man with deer antlers. I bought these many years ago because I thought they were funny. Now I find it funny that I found them to be so funny! Also in my lowbrow collection is a painting on canvas of a disgruntled gutter punk by Chris Miller and two rather unappealing female portraits painted by Judith Ann Moriarty from her Clampett Series, subtitled Real Women Pack Heat. Another work that embodies my off-kilter sense of humor is a gun-shaped pillow. These works are on display in a spare bedroom alongside a gold and black spray painted stencil piece by New York muralist, Logan Hicks. With the exception of the Stonehouse, I purchased these works from Milwaukee’s Lucky Star and Hotcakes Galleries back in the day. The mantel featuring Jeremy Wolf's hare mask. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. Nicole's bunny wall of drawings, etchings and other reproductions. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. As I mentioned before, I have a growing collection of rabbit tchotchkes and rabbit-themed artworks. Our mantel is a rabbit shrine with the centerpiece being a large papier-mâché hare mask by sculptor, Jeremy Wolf. It is mounted on the wall like a trophy head. Below it are various rabbit figurines like an antique stuffed Steiff toy, a beeswax bunny candle, a cookie jar and a piece of driftwood remarkably resembling the animal. Next to the mantel is my wall of 2D bunnies, hung salon style, including a pencil drawing and a few etchings by various local artists, a ceramic tile, an old English tapestry reproduction, and perhaps the most famous hare in art history—a reproduction of the famous Durer print. Nicole's Easter cabinet is filled with bunnies. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved. On and endnote, one of the very first encounters I had with my now husband, metal sculptor, Bill Reid, also involved a rabbit. He was delivering new works to Tory’s gallery and brought in a monstrous sculpture featuring a life-sized man, laying on his back, being mauled by a giant, saber-toothed rabbit. My first thought upon seeing this abomination was, “What sick mind would come up with that?” Turns out we share the same sense of humor. The Rabbit Eating Astronaut holds a place of honor in our living room. While my bunnies are at times in friendly competition for display space with Bill’s sculptures, we’ve been able to maintain a happy balance for 13 years now. The kitchen wall features several drawings, including one Nicole's brother did when he was a boy. Photo courtesy of Nicole Reid. All rights reserved ~Nicole Reid, December 2020

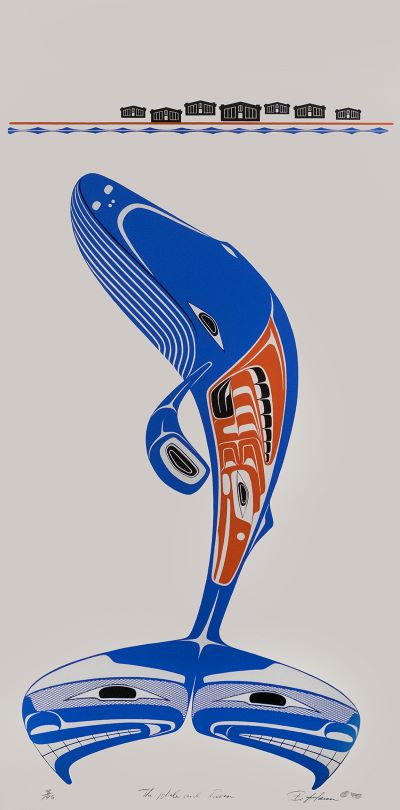

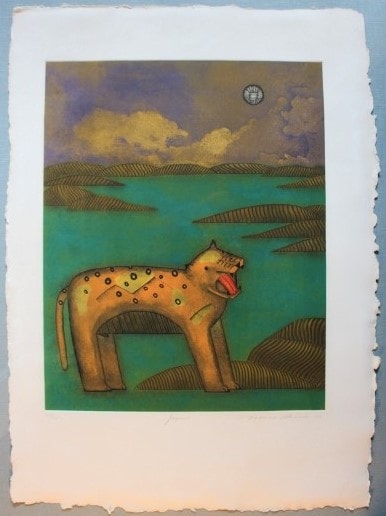

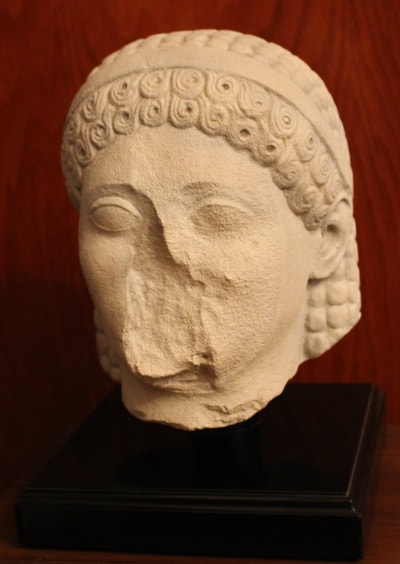

Editor’s Note: Bob Sieger is respected in the artworld. Originally from Kenosha, he worked in the Antiquities Conservation Department at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles for many years. More recently, he brought his expertise back to Milwaukee where he consults with local museums and private collectors on mounting and other specialized needs. Sieger also assisted with facility design during the Guardian building renovation. He recently told me about his personal art collection and provided preservation tips learned from his experience at the Getty. Part I – Personal Collection What do you collect and why? My collection is very small; everything in it was acquired because it appealed to me and, importantly, because I could afford it. It's a mix of things, sculpture; prints; pastels; paintings-oil, acrylic, and gouache; photographs; a few decorative arts furniture pieces; and antiquities, primarily artifacts. Every piece I own evokes memories and emotions: people; places; periods in my life. To me it's similar to walking past a bookcase and having one particular title take me back to the work: the story; the style; the time; the place; everything that made me read and keep that book. That, to me, is one of the best things about owning art; each piece is a part of personal history. The Whale and the Raven by Barry Herem is one of the first pieces Sieger purchased. Photo courtesy of Stonington Gallery and the artist. All rights reserved. I don't know when I actually began what could be termed 'collecting.' Like many people, when I was in school it seemed as though I would move every six months or so. I think maybe when I started being careful to not lose any art during a move could be construed as the starting point. Keeping and caring for the pieces I owned became important. I never consciously attempted to amass a collection; it was always about the individual piece. Sometimes it was the place, like a tiny gallery in Sitka, Alaska where, in 1982, I purchased a serigraph titled, "The Whale and Raven," animals sacred to all Native Alaskan tribes. Or 1993, in a park outside the Bazaar De Sabado in Mexico City where I bought a beautiful print titled "Jaguar" from the artist, Mario Romero, who was showing his work in a small temporary stall. At the time of the purchase in Sitka I had no understanding of the importance of provenance. For this reason, I got no information on the artist or their work from the gallery. The signature on the piece is illegible, and although I've tried to find information online, I hadn't been able to determine the name of the artist. The editor of this piece, Christine Anderson, was able to find the artist. His name is Barry Herem and he works in wood, glass, paper and steel. Jaguar, print by Mario Romero purchased in a market in Mexico City. Photo courtesy of Bob Sieger and the artist. All rights reserved. How do you safely display and/or store your collection? I attempt to follow, as closely as possible, the museum display and storage standards of trying to maintain an ambient temperature of around 70 degrees, and a RH (Relative Humidity) of 50%. I'm also very conscious of keeping any sensitive pieces away from sunlight and limiting their exposure to UV. With a broad mix of objects there isn't any perfect, maintainable climate; some pieces, like metal sculpture do best in a low RH, 30-40%. Other pieces, like works on paper and wooden objects would ideally have a somewhat more humid environment. One of the most important factors in displaying or storing art is that the conditions remain relatively stable, avoiding rapid changes in temperature and RH. What has been most challenging for you in developing your collection? The primary constraint to my collecting, which is a blessing and a curse, is having limited resources to purchase art. This is not all bad because I tend to be a bit of an impulse buyer and have experienced buyer's remorse on a few occasions. Do you have advice for new collectors? I would advise anyone thinking of beginning to collect to buy what you love. Keep records of all the information you can gather about the artist and their career. And keep the receipt. If you have the time and the means learn as much as you can about art in general, and specifically, what you wish to collect. Knowledge of art can only enhance your appreciation. Part II – J Paul Getty Museum What is the focus of the collection you worked with? I worked for many years in the Antiquities Conservation Department at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The Getty's antiquities collection was primarily Greek and Roman, with a few Coptic pieces. The antiquities were almost exclusively 3D objects, art and artifacts, with some 2D material such as frescoes and mosaics. Who was your audience and how did the collection interest them? At the Getty Museum my assumption was always that our audience was generally comprised of that small percentage of the public that had an interest in art and artifacts. The Getty collection was eclectic, originally it was limited to only what interested J. Paul Getty himself. He collected Decorative Arts, Antiquities, Sculpture, Drawings and Paintings. Other than the Antiquities the focus of his collecting was Western European. There was likely a percentage of our audience who were there simply due to a fascination with the Getty name and fortune. It was always gratifying to meet a visitor who was genuinely interested in ancient art and knowledgeable about the pantheon it depicted. An aerocast copy of the original shown to illustrate mount. What was the biggest challenge concerning the collection? How did you safely display and/or store high-risk pieces from the collection?

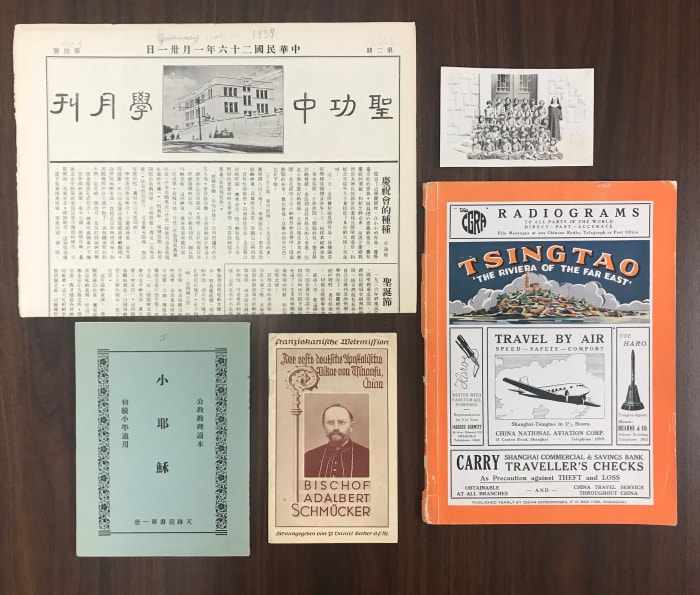

Seismic mitigation. Earthquakes were the single most significant threat to the collection. We were fortunate to be very well-funded. As a result, we had less time constraints than other museums, and we were able to research the best possible ways to protect all types of objects. One result of this research was a base isolation system that was used to decouple large objects from most of the horizontal energy emanating from an earthquake. We designed the isolator and patented it to prevent others from building them for profit. We shared the design and technology, for free, with several other institutions. Later I modified the design and scaled it down in order to use it with much smaller objects as well as small pedestals. All the objects were displayed or stored in a way that safeguarded them as much as possible from earthquake damage. We realized that nothing is truly earthquake-proof, but there are many ways to display or store objects to so as to be very earthquake-resistant. For objects that were robust and could withstand earthquakes as long as they didn't fall, we would attach them to the walls or showcases so they would move with the building during an earthquake. The building had been inspected by seismic engineers and was found to be very strong and unlikely to collapse during an event. More fragile objects needed to supported but decoupled from the seismic input. Our display pedestals were designed to slide rather rock or tip. The only problem with this method was often the curators would move the pedestals closer to the wall and I would have to follow behind them, moving the pedestals away from the walls to allow them to move in all directions. The entire first floor of the Getty Villa Museum was open to the outside air which, due to its proximity to the ocean, was high in salts. To guard against rust which could weaken supports, we generally relied on nonferrous metals, such as aluminum and brass, or stainless steel for our mounts. Like most art museums, the climate was controlled as closely as possible, again trying to maintain an even temperature and relative humidity. ~Robert Sieger The steeples of two landmarks on Milwaukee's south side: St. Joseph Chapel and the former St. Lawrence Church, now home to Notre Dame School of Milwaukee. Over the years, many of the sisters of SSSF taught at St. Lawrence and students crossed the street to minister in Chapel as altar servers at morning Mass. Downtown Milwaukee and Lake Michigan can be seen in the background. Photo courtesy of SSSF. All rights reserved. After a disastrous fire of the original motherhouse in Milwaukee’s Burnham Park neighborhood, the School Sisters of St. Francis rebuilt their motherhouse, St. Joseph Convent in 1891. Over the years, more handsome buildings were added to the campus, including the magnificent Italian Romanesque Revival St. Joseph Chapel completed in 1917 and the Sacred Heart retirement home was renovated more recently. Since its founding, the SSSF have preserved Archives for study by the religious community, relatives of the sisters, and for scholars and members of the public. The rich trove contains works published by members of the SSSF community, reference materials, historical documents, textiles, objects, and more. Eva Stefanski, archivist for SSSF recently discussed the diverse collection and her ongoing work to preserve it. Sister Julie Knotek, unidentified sister, Sister Ann Marie Dressler and Sister Frances Recker (left to right) at St. Lawrence School across Layton Blvd. from St. Joseph Convent, Milwaukee. Photo courtesy of SSSF. All rights reserved. Current display of items in the Archives from the original Motherhouse in Campbellsport. Photo courtesy of SSSF. All rights reserved What is the focus of the collection you oversee? The School Sisters of St. Francis have a long and rich history lasting almost 150 years. The worldwide membership of the community marked its peak of 4,140 members in 1965, and today, with roughly 640 sisters and 170 lay associates worldwide, the congregation continues to serve in North America, Central and South America, Germany, Switzerland, India and Tanzania. The Archives focuses is on preserving materials that chronicle that history along with documents and artifacts that demonstrate the mission, charism, and administration of the community today. We preserve the materials to aid in the congregation’s current planning and decision making as well as to illustrate the history of the community and enable genealogical and historical research. Mother Corona with the faculty of St. Joseph Middle School in Tsingtau, China in 1936. Photo courtesy of SSSF. All rights reserved Who is your audience and how does your collection interest them? Our audience is more varied than one might initially think. While many of our patrons are the Sisters themselves, we get many other types of requests. People often don’t realize that the Sisters lead accomplished professional lives just as lay people do. We are contacted about books they have written, music they have composed and recorded, and art they have created. Additionally, the Motherhouse, the chapel and the surrounding buildings are a historic landmark, so we get many questions about the history of the buildings and grounds as well as the architecture. Also, many requests come for more information about the history of different missions all over the country. The history of the Sisters is deeply embedded in the history of many other parishes, schools, hospitals and communities. Finally, we support frequent genealogy requests. Many lay people with ancestors who belonged to religious congregations want to understand the lives and accomplishments of these women. View of St. Joseph Chapel from the loft. Photo courtesy of SSSF. All rights reserved. What has been the biggest challenge concerning the collection? While working with an international collection is exciting, it’s also challenging. The foreign provinces such as Germany and Honduras have their own archival material in addition to what we have in our collection. Visibility across collections is low, so it can be hard to know where gaps exist and how all of the materials fit together to tell the larger story. Until we are fully able to increase access through digitization, the only way to get the full impact of the scope of our collection is to travel to all of the collecting sites. Alvernia High School Chicago Students lining up for lunch at Alvernia High School in Chicago in 1943. The all-girls school was the first that the School Sisters of St. Francis sponsored and built, opening in September 1924. Photo courtesy of SSSF. All rights reserved. How do you safely display and/or store high-risk pieces from the collection? In Archival work, it is all about what we call “archival housing”. This term refers to the products and materials we use to store and maintain pieces in the collection. Archival housing is not just for rare and fragile items – it ensures the longevity of even simple business documents through the use of things like acid-free folders and boxes. Disaster planning is also critical. Finding the best locations to store collections includes understanding the risks around the potential for things like leaky pipes and mold and having a process that enables you to act quickly if risk becomes reality. Photo and paper ephemera from the Mission in Tsingtao, China in the 1930’s and 1940’s. Photo courtesy of SSSF. All rights reserved. Archival Storage Boxes help preserve fragile documents, photographs, and ephemera. Photo courtsy of SSSF. All rights reserved. What advice do you have for collectors who are just getting started?

My advice for collectors is less about collecting and more about preservation. As an archivist, one of my primary concerns is how to ensure the longevity of the collection under my care. This should be a concern of any collector. Take time to understand the materials that compose what you are collecting and learn about the best conditions for storage and display such as how much light, humidity, and heat are appropriate. Consider not collecting a piece if you are not equipped to care for it or donating a piece to an institution that has the means to ensure its care. Decide early if you want your collection to outlive you and take measures along the way to ensure it will last for many years to come. ~Eva Stefanski, Archivist for School Sisters of St. Francis, October 2020 Editor’s note: Prior to the pandemic, I had the opportunity to tour the campus with archivist Eva Stefanski and Alfons Gallery director Valerie Christell. The historic buildings are filled with beautiful architectural details and fine art made and collected by the sisters. Since all buildings are closed to visitors for safety reasons, explore the SSSF website to learn more about their leadership in the arts and view their video tour of St. Joseph Chapel. Lois Bielefeld is a series-based artist working in photography, audio, video, and installation. Her work continually asks the question of what links routine and ritual to the formation of identity and personhood. Editor's note: we originally invited Lois to talk about her collection of local artwork, after getting tantalizing glimpses in the background of her House, Hold series. However, after learning that she "collects" hundreds of portraits to make her series-based work, we wanted to learn more about her process. Self-portrait by Lois Bielefeld. Photograph courtesy of the artist. All rights reserved. Currently splitting her time between Chicago and Los Angeles, Lois was born in Milwaukee, WI and has lived in Rochester, Brooklyn, and Oakland. She is working on her MFA (2021) at California Institute of the Arts. Lois is a recent empty nester as her daughter attends the University of Minnesota. Besides photography, she feels passionate about traveling, hiking, eating, swimming and bicycling adventures with her wife. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art in New York City, the Museum of Wisconsin Art, Saint Kate Arts Hotel, The Warehouse Museum and The Racine Art Museum in Wisconsin. Bielefeld has shown at The International Center of Photography in New York City, The Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, The Charles Allis Art Museum, and Portrait Society Gallery in Milwaukee. What do you collect and why? In 2008 I started my first series-based work, The Bedroom. I was interested in how this intimate space reflected a person and how this manifested in the resulting photograph. This was the beginning of me collecting although I didn’t realize that I was creating these vast collections of photographs around specific themes until recently. The Bedroom evolved into 103 portraits and formulated many of my working practices that I still hold onto today. At the time I saw these portraits as collaborative and a sort of non-scientific ethnographic study. Today I see my work as constructed performances by my participants for the camera. Here is a curious break down of part of my collection by series, time and volume: 2008-2012 The Bedroom (103 photographs) 2012-2013 Conceal Carry (30 photographs) 2012 Lunch Portraits (71 photographs) 2013-2014 Androgyny (58 photographs) 2013-2015, 2017 Weeknight Dinners (86 photographs) 2015-2017 Neighborhood (108 photographs) 2018-current Celebration (11 celebrations) 2018-current New Domesticity (54 photographs) 2019-2020 Broom Studies (120 video studies, 8 hour video piece) 2020 House, Hold (31 photographs) Lois Bielefeld, Steven, Manhattan. 2008 from The Bedroom (the very first photo in the series) Photograph courtesy of the artist and Portrait Society Gallery. All rights reserved. So why? Why am I doing this and why has this act of making within a series in a serial manner so important to me and my practice? I think it is because I’m deeply curious about a specific topic (i.e. gender identity, the evening meal, or domesticity) and I dig into this idea over and over again to become informed by my participants habits, rituals, aesthetic, their thoughts and experiences, and their spaces. Fundamentally, my work continually asks the question of what links routine and ritual to the formation of identity and personhood. I think this is the “why” behind these collections. Lois Bielefeld, Wednesday: Willie Mae. 2013 from Weeknight Dinners Photograph courtesy of the artist and Portrait Society Gallery. All rights reserved. When and how did you get started? I started making photographs when I was a child- initially I had a point and shoot camera that I’d get developed at Walgreens. In high school I was gifted a Pentax K1000 and my folks helped me set up my own black and white darkroom. At this time, I puttered around with the magic of photography-- photographing anything and everything. I studied photography in undergrad at Rochester Institute of Technology graduating in 2002. But it wasn’t until 2008 that I started making series-based works and I think around 2011 that I started to actively pursue my art practice. Lois Bielefeld, Phillip. 2014 from Androgyny Photograph courtesy of the artist and Portrait Society Gallery. All rights reserved. Serra Family Sunday Pasta Lunch. 2018 from Celebration Photograph courtesy of the artist and Portrait Society Gallery. All rights reserved. How do you safely display and/or store your collection? This changes depending on the gallery or institutional space. Each time I show the work it takes on new form based on the context of each space, the current time period shown (what’s happening in the world), and the relationality of other works in the space and the conversation that occurs between them. Sometimes I show the work framed and sometimes I share the work as loose prints hung directly on the wall which gives the prints a much more charged sense of objecthood and vulnerability. Additionally, there is the complex method of archiving digital files. I keep 3 backups of all my files and try to keep one of the three drives offsite. I also do all my own printing (digital) and my framed work currently is overtaking a room at my parent’s home that we’ve recently renamed “The Equipment Room.” Lois Bielefeld, Peter, Eliza, Eula and Abigail. 2018 from New Domesticity Photograph courtesy of the artist and Portrait Society Gallery. All rights reserved. What has been most challenging for you in developing your collection? I think every individual series has its own challenges- sometimes it can be very difficult to find participants, other times I tire of schlepping equipment around, but most often I would say the consistent difficulty is getting the work out there. I love making the work- it gives me a sense of purpose and vivaciousness! But I really don’t care to promote myself, apply to calls, and networking. This labor is the most challenging to me. Lois Bielefeld, Broom Study #11 Still. 2019 Photograph courtesy of the artist and Portrait Society Gallery. All rights reserved. Lois Bielefeld, Broom Study #69 Still. 2019 Photograph courtesy of the artist and Portrait Society Gallery. All rights reserved. Do you have advice for new collectors? For art collection, collect work that moves you- that you keep thinking about and has a staying power. Start by getting familiar with your local art scene by going to the local galleries, different institutions- museums and universities. Ask an artist for a studio visit to get a behind the scenes look at their process and to see the work in person. Supporting the local art scene is so crucial and commendable. And definitely consider the work of students and emerging artists. Lois Bielefeld, May 29: When Lois doesn't have a pocket, she uses her waistband to hold tissues. When Jackie doesn't have a napkin, she wipes her fingers on her sock. 2020 from House, Hold. Photograph courtesy of the artist and Portrait Society Gallery. All rights reserved. ~Lois Bielefeld, September 2020

Photographic materials are common in personal collections and also highly susceptible to damage in poor storage conditions. Fluctuations in temperature, relative humidity, and light levels can all lead to physical and chemical deterioration of photographs and photographic materials. Similar to paper documents, photographs should be stored in buffered archival folders, separated by like materials in a climate controlled room. Unstable or highly combustible materials, such as silver nitrate negatives, should be stored carefully and in isolation from other collections. It is also important to store prints separate from negatives to protect against the potential of complete loss during a disaster and to protect against chemical deterioration from off-gassing.

If you have questions about the condition of your photographic materials or need a safe place to store them, please email [email protected]. We are here to help! #artcollection #artcollecting #bestartstorage #preserveart #artstoragetips #protectart, #keepartsafe #secureyourcollection #guardianfineart #archivalmaterials #archivalphotographstorage Do you have important documents, records, or works on paper that you store at home? Take this time of social distancing as an opportunity to implement proper storage and preventive conservation measures for those objects. Paper is inherently fragile and should be stored in acid-free boxes, folders, envelopes etc. Specific recommendations for storage of paper objects vary based on size and type of paper. Overall, storing paper objects in buffered folders within archival boxes on proper shelving is optimal. This creates a micro-environment that protects against light damage, dust, and fluctuations in temperature and humidity.

If you have questions about the condition of your paper objects, need archival storage supplies, or need a safe place to store them, please email [email protected]. We are here to help. #bestartstorage #preserveart #artstoragetips #Protectart #keepartsafe #secureyourcollection #guardianfineart #archivalmaterials #storageforpaper |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed